Noise Contrastive Estimation (1/3) - Binary NCE

Written on January 11th, 2024 by Henry Bourne

Noise Contrastive Estimation

This is the 1st in a series of 3 blog posts I will be writing on Noise Contrastive Estimation (NCE). NCE is an estimation technique used to train a model in an unsupervised way, that means with no teaching signal - for example to perform supervised classification the teaching signal would be the class label corresponding to each training example.

NCE is often referred to as a self-supervised learning technique, what differentiates it as self-supervised learning is that it uses the data itself to provide the teaching signal. Within self-supervised learning there are two main approaches; generative and contrastive. Generative learning is where the model is trained to generate the data itself, for example a generative model trained on images could be trained to generate images. A famous example of a generative learning technique is the Auto Encoder, introduced by Kingma and Welling in their paper ‘Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes’. Contrastive learning is where the model learns by contrasting the data with other ‘data’ (this could be observed data, noise or synthetic data). Contrastive learning is where the model learns by contrasting the data with other ‘data’ (this could be observed data, noise or synthetic data).

NCE is a contrastive learning technique and is the most well-known. It was first introduced in 2010 by Gutmann and Hyvarinen in their paper ‘Noise-contrastive estimation: A new estimation principle for unnormalized statistical models’.

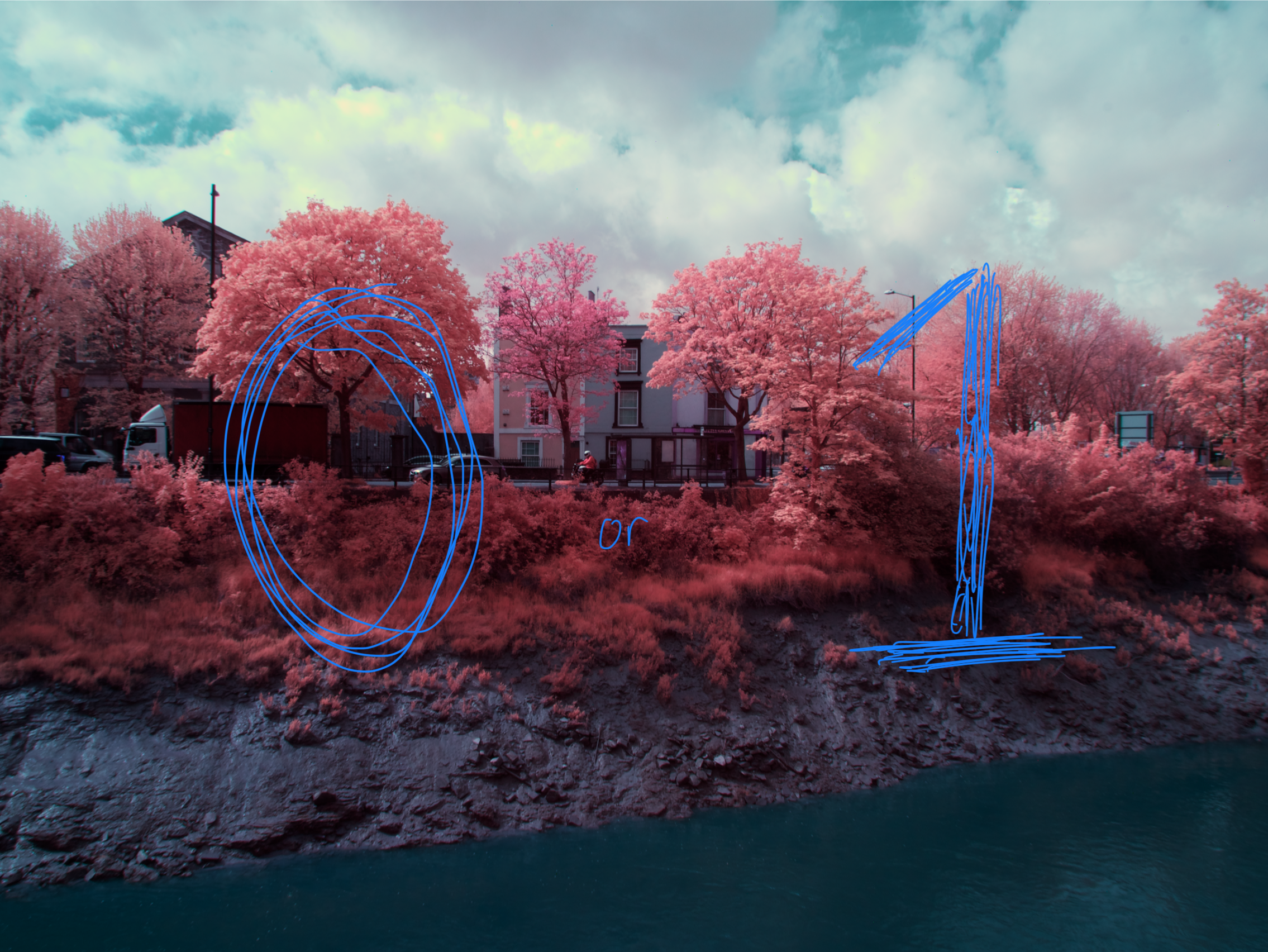

In this blog post we will focus on binary NCE which is the way NCE was introduced in the seminal paper above. In the next blog post we will look at how NCE can be extended to the multi-class case and in the final blog post we will look at a special case of NCE called InfoNCE which is used in the popular self-supervised learning technique called ‘Contrastive Predictive Coding’ introduced in 2018 by Oord, Li and Vinyals in ‘Representation Learning with Contrastive Predictive Coding’.

This blog post aims to be a well laid out and easy to follow rigorous introduction to NCE. This blog post essentially aims to regurgitate the seminal paper into something hopefully more easy to follow. The next blog posts will build on from my writing in this post to expand NCE to the multi-class case (Ranking NCE) and later to information NCE (infoNCE). If you are looking for a more intuitive introduction to NCE or contrastive learning I would recommend looking elsewhere, we will be looking at the maths powering NCE in this blog post!

I am aiming to keep these blogs evolving, so if you have any feedback on this blog or others please leave a comment and I’ll aim to address it!

Binary NCE

Let’s dive straight in! NCE is an estimation principle for parameterized statistical models. That means given a parameterized statistical model and some observed data we can use NCE to estimate the parameters of the model. We can use Binary NCE if we have the following setup:

- \(p_{d}(\cdot)\), Some probability distribution we want to estimate, we also assume we have a collection of samples/observations from this distribution.

- \(p_{m}(\cdot;\alpha)\), A probability model parameterized by \(\alpha\).

- Assume \(\exists \alpha^{*} \: \text{such that} \: p_{d}(\cdot) = p_{m}(\cdot; \alpha^{*})\).

Throughout I’m going to put assumptions in green so that they are easily identifiable! Assumptions are important and can often be hard to spot in papers, so I will try to make them clear.

Why not Maximum Likelihood Estimation?

An obvious solution to such a problem would be to use Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) as it has been used extensively, is reliable and has great theoretical properties. For example, it achieves the Cramer-Rao lower bound which is the lowest possible bound an unbiased estimator can achieve for its variance/MSE.

Let’s consider what our parameterized model looks like: \(\begin{array}{l|l} p_{m}(\cdot;\alpha)=\frac{p_{m}^{0}(\cdot; \alpha)}{Z(\alpha)} & \text{where,} \: Z(\alpha) = \int p_{m}^{0}(u; \alpha) du \end{array}\)

Computing \(Z(\alpha)\) is often intractable (or at least very expensive to compute) if an analytical solution is not available and/or if the possible values that the input can take are large. This is because we have to integrate (or sum if discrete) over every possible value the input can take for each value of \(\alpha\) we would like \(Z(\alpha)\). Images are a great example as the number of possible images is very large even for very low-resolution images.

In these cases we can’t use the MLE 😞.

Let it self-normalize!

If we again consider our parametric model and take the log we have:

| $$ \begin{aligned} &{} p_{m}(\cdot;\alpha) = \frac{p_{m}^{0}(\cdot; \alpha)}{Z(\alpha)} \\ & \Rightarrow \log p_{m}(\cdot; \theta) = \log p_{m}^{0} (\cdot ; \alpha) +c \end{aligned} $$ | $$\text{Where, } \\ \theta = \{\alpha, c \}, \\ \text{c an estimate of} -\log Z(\alpha)$$ |

What we’ll do is just add ‘c’ as a parameter of our model and estimate it along with all our other parameters (and will now use \(\theta\) to refer to our new set of parameters), making the model self-normalising. Pay attention to the fact that we now use \(\theta\) to denote our model parameters, where \(\theta\) now includes \(c\) as a parameter alongside our original model parameters \(\alpha\).

We will talk more about assumptions needed for this to work in the next blog post of this series.

So assuming that we can infer the normalizing constant we no longer need to compute \(Z(\alpha)\) anymore!

But … you may be asking, why can’t we take the self-normalizing assumption and then just apply MLE? The reason is that we can make the likelihood arbitrarily large by making c arbitrarily large. So … let’s find out how we can make this work with Binary-NCE!

Side-stepping the problem (where the noise comes in)

Fitting \(p_{m}(\cdot ; \theta)\) directly can be difficult if our model and data is complex and high-dimensional. Let’s not do this and instead try maximise a statistic that is easier to compute but achieves the same thing. Let:

- \(X=(x_{1}, ..., x_{T})\), be the observed data, distributed \(p_{d}(\cdot)\).

- \(X' = (x'_{1},...,x'_{T})\), be artificial noise, with distribution \(p_{n}(\cdot)\).

And let’s turn our problem into a binary classification problem of guessing whether a sample comes from \(p_{d}(\cdot)\) or\(p_{n}(\cdot)\).

We can assess how likely some sample, \(u\), is to have come from our estimate of the pdf, \(p_{m}(\cdot;\alpha)\), compared to from our noise distribution, \(p_{n}(\cdot)\), by evaluating the following density ratio:

Notice that if \(u\) is more likely to have come from \(p_{m}(\cdot;\alpha)\) than \(p_{n}(\cdot)\) then this ratio will be greater than 1 and vice versa.

Taking the \(\log\) we can rewrite this:

Now it’s in terms of our probability model parameterized by \(\theta\) and is in an easily interpretable and computable form (just the difference between two \(\log\) probabilities which we can both easily calculate, assuming an analytical expression for the pdf’s).

Let’s define a function to represent the log density ratio we just derived:

This represents how likely \(u\) is to have come from either the ‘real’, \(p_{d}(\cdot)\), or noisy, \(p_{n}(\cdot)\), distributions. We would like to represent this as a probability (between 0 and 1) so we put it through the logistic function:

Now we have a probability that \(u\) comes from the ‘real’ distribution, we need some way of measuring how well our classifier is doing so that we can optimize the parameters.

We will use the following objective function:

This objective function is similar (up to a factor of \(1/2T\)) to the objective function for a supervised binary classification problem with cross entropy loss where you are trying to predict a label that’s 1 if the sample comes from the ‘real’ distribution and otherwise is 0. The fact that this objective is so similar to the cross entropy gives some understanding for why the above objective function works at classifying a sample as ‘real’ or noise. Check out section 2.2 in ‘Noise-contrastive estimation: A new estimation principle for unnormalized statistical models’ for a more full explanation. In a later blog post I’ll show mathematically how such an objective function actually leads to us estimating the density ratio we discussed above.

Ancillary objective functions for theoretical analysis

We now will quickly define some ancillary objective functions which I will reference in our assumptions and theorems in the next few sections.

The following objective function is what \(J_{T}(\theta)\) is shown to converge to in probability in Theorem 1.1(by the weak law of large numbers):

We introduce it here to make our theorems more readable in the next sections.

We denote by \(\tilde{J}\) the objective \(J\) above seen as a function of \(f(\cdot) = \log p_{m}(\cdot ; \theta)\):

This just makes clear the model we are optimizing with respect to the objective function.

Assumptions for our theoretical guarantees

We now introduce some assumptions that we will need to make in order to prove our theoretical guarantees for NCE. The assumptions and theorems are similar to those we find for MLE and appear in the binary NCE paper ‘Noise-contrastive estimation: A new estimation principle for unnormalized statistical models’.

Assumption 1.1

\(p_{n}(\cdot)\) is non-zero whenever \(p_{d}(\cdot)\) is non-zero.

Assumption 1.2

\(\text{sup}_{\theta}| J_{T}(\theta) - J(\theta)| \rightarrow^{P} 0\)

Assumption 1.3

| $$\mathcal{I} = \int g(x) g(x)^{T} P(x)p_{d}(x)dx$$ | Where, $$P(x) = \frac{p_{n}(x)}{p_{d}(x)+p_{n}(x)},$$ $$g(x) = \nabla_{\theta} \log p_{m}(x;\theta)|_{\theta^{*}}$$ |

We will discuss more what these assumptions mean and how easy they are to fulfill in the ‘Discussion’ subsections in the next section (Theoretical Properties).

Theoretical Properties

We now introduce some theoretical properties of NCE. The proofs of these properties can be found in the paper ‘Noise-contrastive estimation: A new estimation principle for unnormalized statistical models’.

These theorems are similar to those we find for MLE and give us some theoretical guarantees for the NCE method. Let’s now dive into what these theorems are, mean and the assumptions they rest on.

Theorem 1.1 - Nonparametric estimation

If Assumption 1.1 holds then, \(\tilde{J}\) attains a maximum at \(f(\cdot) = \log p_{d}(\cdot)\) and there are no other extrema.

Discussion of Theorem 1.1:

This theorem shows that the pdf, \(p_{d}(\cdot)\), can be found by the maximization of \(\tilde{J}\). A key thing to notice is that the maximization is performed without any normalization constraint for \(f(\cdot)\). This contrasts heavily with MLE where we must have \(\exp(f)\) integrate to 1. We also find that Assumption 1.1 is pretty easily fulfilled. For example, if \(p_{n}(\cdot)\) is a Gaussian with mean 0 and variance \(\sigma^{2}\) then \(p_{n}(\cdot)\) is non-zero whenever \(p_{d}(\cdot)\) is non-zero.

Theorem 1.2 - Consistency

If Assumption 1.1, Assumption 1.2, Assumption 1.3 hold then, \(\hat{\theta}_{T} \rightarrow^{P} \theta^{*}\).

Discussion of Theorem 1.2:

This theorem tells us that \(\hat{\theta}_{T}\) (value of \(\theta\) that globally maximizes \(J_{T}\)) converges to \(\theta^{*}\) (the optimal value for \(\theta\)), leading to a correct estimate for \(p_{d}(\cdot)\) as sample size \(T\) increases.

This means it tends in probability to both a correct estimate of the un-normalized pdf, \(p_{m}^{0}(\cdot ; \alpha)\), and the normalization constant, c. This is impossible when using the maximum likelihood!

Again Assumption 1.1 is easily fulfilled. Assumption 1.2 and Assumption 1.3 have similar counterparts in MLE. Assumption 1.2 means we need \(J_{T}\)to converge uniformly in probability to \(J\). Assumption 1.3 means we need the objective landscape of \(J_{T}\) to be fairly peaky around the value of \(\theta^{*}\).

Theorem 1.3 - Asymptotic normality

\(\sqrt{T} (\hat{\theta}_{T} - \theta^{*})\) is asymptomatically normal with mean 0 and covariance matrix \(\Sigma\). Where, \(\Sigma = \mathcal{I}^{-1} -2\mathcal{I}^{-1} \left[ \int g(x) P(x) p_{d}(x) dx \right] \times \left[\int g(x)^{T} P(x) p_{d}(x) dx \right] \mathcal{I}^{-1}\)

Discussion of Theorem 1.3:

This theorem describes the distribution of the estimation error as our sample size tends larger It says that the distribution is \(\mathcal{N}(0,\Sigma)\), which means the NCE is an unbiased estimator.

Corollary 1.1 - Asymptotic efficiency

For large sample sizes \(T\), the mean squared error \(E|| \hat{\theta}_{T} -\theta^{*} ||^{2}\) behaves like \(tr(\Sigma)/T\).

Discussion of Corollary 1.1:

This corollary says that the mean squared error starts to resemble the sum of asymptotic variance of all the parameters divided by the number of samples.

Choosing the noise distribution

Ideally we want a noise distribution that:

- Is easy to sample from.

- Allows for an analytical expression for the log pdf (so we can evaluate \(J_{T}(\theta)\) without issues).

- Leads to a small MSE, \(\mathbb{E} \| \hat{\theta}_{T} -\theta^{*} \| ^{2}\).

Intuitively we want \(p_{n}(\cdot)\) to be similar to \(p_{d}(\cdot)\) otherwise we may not learn the structure of data (a theoretical argument for this is given in the paper ‘Noise-contrastive estimation: A new estimation principle for unnormalized statistical models’). One method for choosing the noise distribution is to first estimate a preliminary model for the data and then use that preliminary model as your noise distribution, \(p_{n}(\cdot)\).

A quick 🌯-up

Wrapping up, we can use NCE to estimate a parameterized statistical model in situations where we can’t use the MLE. The MLE is great as it has been extensively used and has very nice theoretical properties. But in this blog-post we show that in fact the NCE also has similar statistical properties! and that these properties rely on similar assumptions. So this is why Binary NCE is great!

Why is it not so great? We will discuss this more when we get onto talking about Ranking NCE in the next blog-post, but, basically we can’t use it if the number of possible values of the random variable we are trying to model is much larger than the number of free parameters. This comes as a result of our self-normalisation assumption. Finding a good noise distribution is also hard! One of the most difficult properties to fill is finding a good noise distribution that has an analytical expression for the log pdf.

(👀 Working on adding a Jupyter Notebook to show binary NCE in action 👀, Will add it here once it’s finished!)